Here is someone who knows what he is talking about. Lindner worked as a teacher for the blind for over forty years, including more than twenty years as head of the von Vincke School for the Blind and Visually Impaired in Soest. For that reason, his book wants to be more than a mere philatelic publication of a “scientific” character. His aim is to address the widest possible audience in a comprehensible language that he intends to familiarise by means of a catchy presentation with the blind and their care, without neglecting the strictly philatelic aspect or foregoing accuracy in the information. And the advanced collector should also get his money’s worth. To say it in advance: the author has succeeded in this balancing act!

The general introduction informs the reader about the basic communication possibilities of blind people and sheds light on the position and importance of blind people in antiquity through the Middle Ages up to the establishment of the first schools for the blind in the late 18th century. The road from the first tactile relief writings to the invention of Braille in 1825 was a long one. At the age of three, Louis Braille went blind as a result of an injury he sustained while playing with an awl in his father’s shoemaker’s workshop. When he was sixteen years old, he developed his own transcription system. He was inspired by a “night writing” system introduced by the military, which enabled soldiers to feel texts in the dark. Braille skillfully reduced this system to a six-dot code, with the help of which 63 combinations for all letters, numbers and punctuation marks could be represented. However, it took another 25 years for Braille to achieve a breakthrough, which occurred shortly before his death when his script was officially approved for teaching in schools for the blind. Today, it is the common system in all countries of the world and is used for a wide variety of languages and scripts, including Arabic, Japanese and, most recently, Tibetan. Sabriye Tenberken developed this version for her students. After studying in Marburg and Bonn, she and her husband founded the first school for the blind in Lhasa in 1998.

The introductory cultural-historical outline leads to a detailed description of the postal treatment of cecograms [< Latin caecus = blind], the international term in postal language for mail of the blind. When the UPU was founded, the fee was still the same as for ordinary letters. In 1886, items sent to the blind were treated as printed matter, which for the first time amounted to a reduction in the fee. At the UPU Congress in Madrid in 1920, it was decided to introduce a special fee for items sent by and addressed to the blind, with a maximum weight that gradually rose to 7 kg. The 1952 Congress in Brussels recommended that items of the blind be sent postage-free, a method which some countries had long since introduced; this meant that a fee was due only for additional services. That regulation was abolished as of 1 January 1966. Germany, however, only partially followed the recommendations and continued to charge for special services.

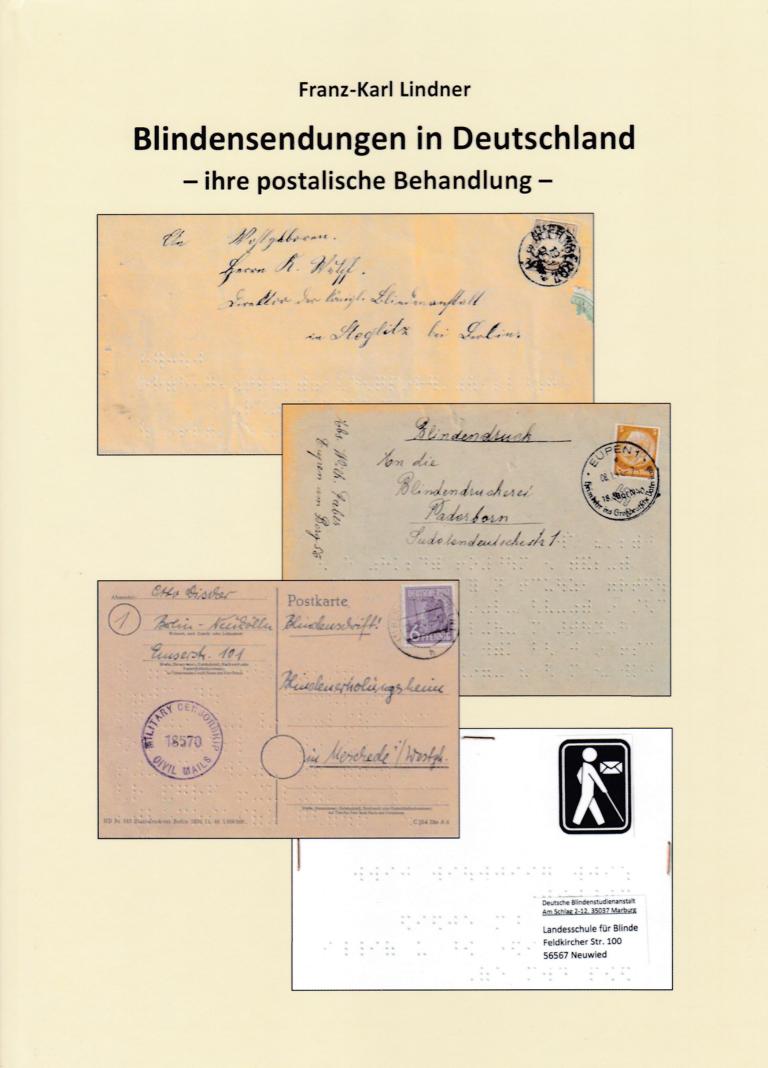

Lindner is convinced that “man is an optically oriented creature” and through sight “gets access to new things much more easily”. This is evident in the design of his book: he likes to use illustrations frequently, wherever possible to scale in the original format of the document. His earliest document – almost all of the items come from his own collection – shows a Berlin local postcard from December 1885. In addition, he is able to present rare uses such as foreign destinations, a record mailing from the Berlin Punktdruck-Verlag or a postage-free reusable blind mailing to the Norddeutsche Blindenhörbücherei. The blind items from the various – sometimes quite short-lived – German-speaking territories deserve special attention. These include a 1938 consignment from the Ostmark [occupied Austria] with the rare 1 Pf franking, uses from the Saargebiet, Sudetenland, Alsace, Eupen-Malmedy, Bohemia and Moravia, the Generalgouvernement, Saarland and the various occupation zones, the GDR and finally the Federal Republic. The repeatedly integrated postage tables are helpful and valuable: often they could only be compiled through time-consuming and laborious research. These overviews of the charges from the different tariff periods alone are worth buying the work!

Until now, mailings for the blind have led a shadowy existence in postal history exhibits. This should be a thing of the past after Lindner’s publication, because in the future jurors will certainly look specifically for cecograms. In any case, the Foundation for the Promotion of Philately and Postal History made the right decision in allowing č financial subsidy for printing the book. This successful first attempt to study the postal treatment of items for the blind in Germany and to document it comprehensively in philatelic terms deserved it!

If you want to look beyond your own nose to find out how mail for the blind is treated all over the world, you will find what you are looking for on the author’s website: www.lindnerfk.de.

Rainer von Scharpen, FRPSL

LINDNER, Franz-Karl Lindner, Blindensendungen in Deutschland – ihre postalische Behandlung. [Blind Man’s Mail in Germany – Its Postal Treatment]. 89 p., A 4, hardcover, thread binding, coloured illustrations, self-published 2022. Price: € 35.00 + postage. Available from the author, Westfälischer-Friede-Weg 21, 59494 Soest, Germany. E-mail: fkl50@gmx.de