In the early days of philately, postal stationery was usually collected as cut-outs and stuck into albums like stamps, probably in view of the fact that postal stationery is in fact nothing other than postage stamps in a special form. In terms of use, however, postal stationery cut-outs are not simply treated as “normal” postage stamps. The relevant regulations on their use vary considerably from country to country. In the literature, the subject has so far been terra incognita.

In the present study, Madhukar and Savita Jhingan tackle the problem for the first time in relation to their home country of India. However, they did not just leave it at a mere series of illustrations, but also dealt with the subject matter in detail, meticulously researching the relevant passages in the postal regulations, which they quote in full in their paper.

The British colony of India received its first postal stationery in 1856 in the form of envelopes with embossed stamps. This was followed a year later by folded letters, known as letter sheets, then postcards in 1879, followed by registered envelopes in 1886 and finally newspaper wrappers in 1895.

In terms of postal regulations, the colony largely followed the mother country. From 1845 to 1870, stationery cut-outs – the first were from Mulready envelopes – were authorised for domestic mail. India too adopted a similar authorisation, but revoked the regulation as early as March 1869, with repeated confirmations of the ban in the following years. From 1 January 1905, Great Britain again permitted the use of cut-outs for normal franking – incidentally, this permission is still valid today – and India again followed the British example. But as early as 1 July 1907, India banned cut-outs once again, and this time for good. The Postmaster General Charles Stewart-Wilson justified the measure at the time as a “means of protection of the mail against private servants”. Items illegally franked with cut-outs were henceforth regarded as unpaid and charged additional postage – apart from the occasional items that slipped through.

The quality and abundance of covers with which the authors document their explanations is impressive. They range from the earliest evidence for the year 1865 to the period after India’s independence (latest example: 1979) and document the regular use from 1905 to 1907 as well as the illegal use thereafter. In addition to these 42 examples, the authors also present items from the feudal states of Gwalior (4), Jaipur (6), Kishangarh (2) and Orchha (1). Even Portuguese India is represented with one example.

The brochure, in an edition of 100 numbered copies, may look meagre with its 40 pages, but it has a lot to offer! It is impressive due to the in-depth research and the rare covers and may serve as an inspiration for many a postal stationery collector to write a comparable study for their collecting area.

Rainer von Scharpen, AIJP

JHINGAN, Madhukar & Savita, Postal stationery of India. Cut-outs used as adhesives. [Ganzsachen Indiens. GA-Ausschnitte, verklebt als Freimarken.] 40 S. A-5, farbige Abb., Softcover. New Delhi (Indien): Stamps of India, 2023. Preis: 35 $ incl. Luftpost-Versand. Bezug: bei den Autoren, 49 D, BG-5, Paschim Vihar, New Delhi 110063, Indien. E-Mail: savitajhingan@yahoo.com.

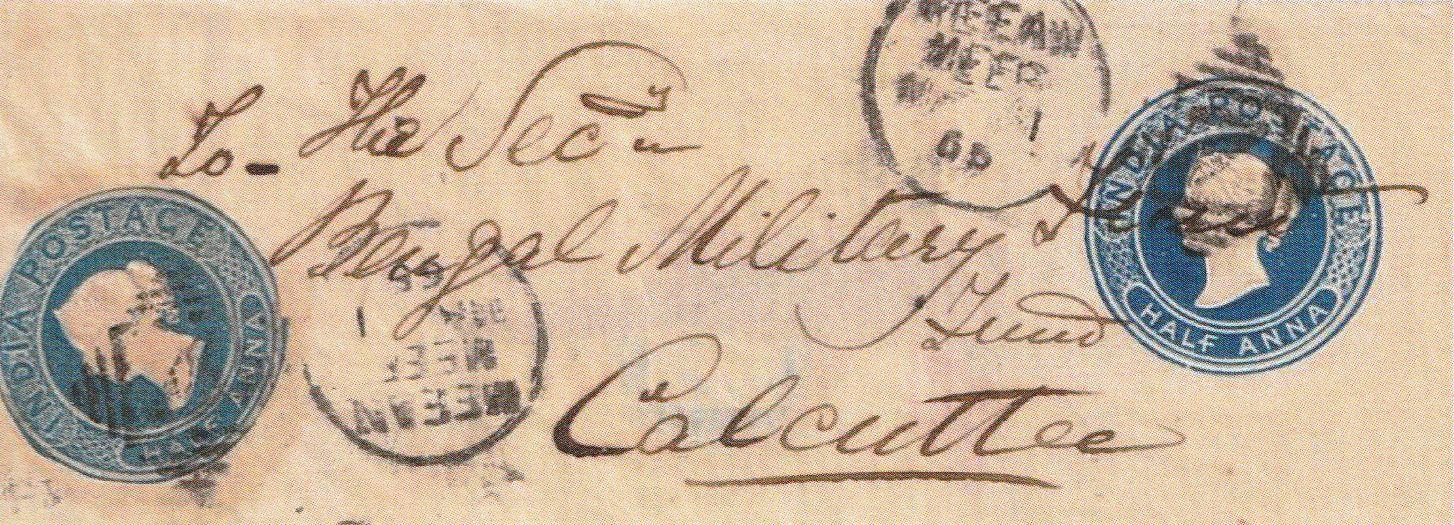

Fig. 2: Stationery cut-out from a ½ Anna Queen Victoria envelope on a stationery envelope with the same image; earliest known use to date, Meean Meer 1865 to Calcutta.

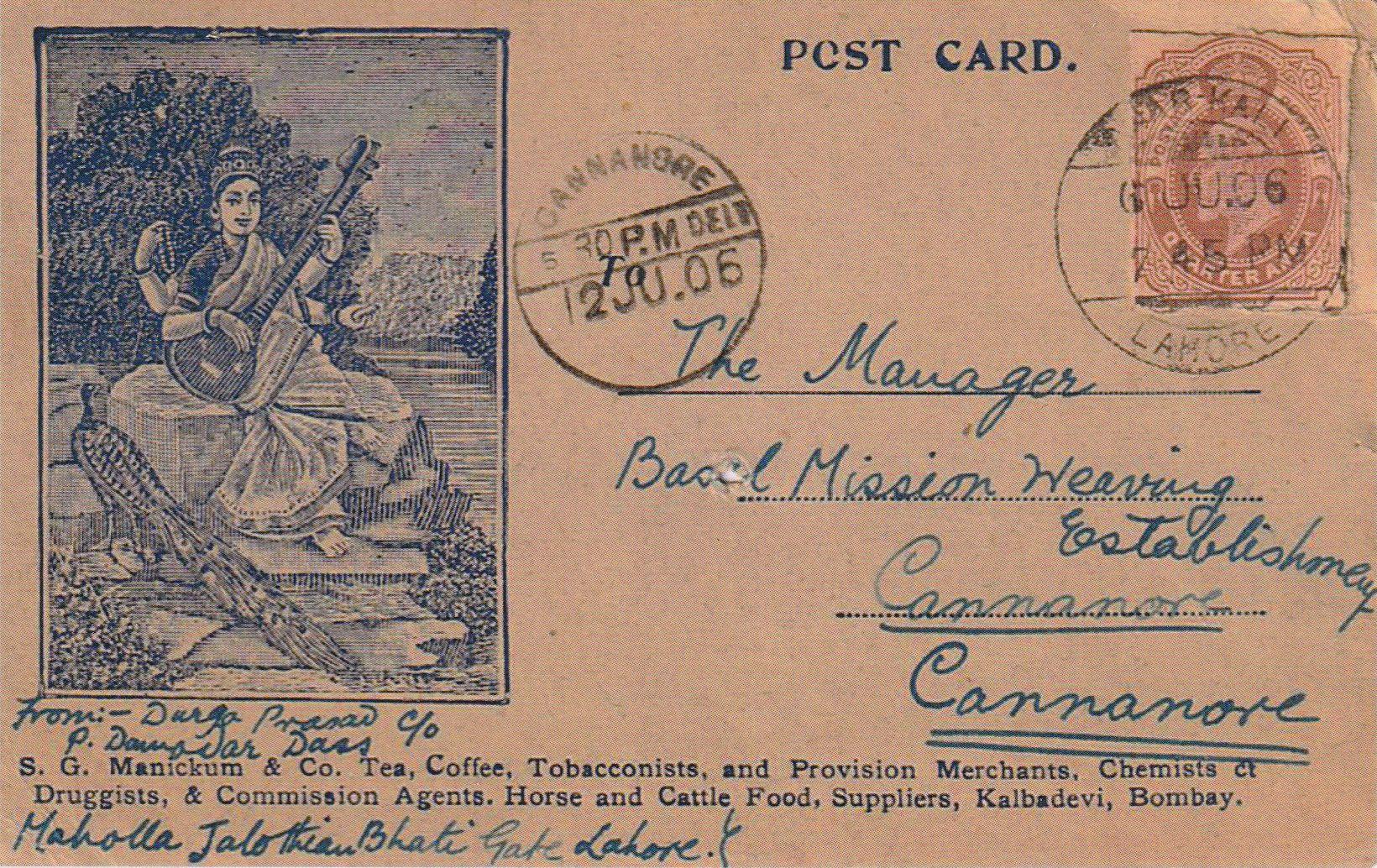

Fig. 3: Stationery cut-out from a ¼ Anna King Edward VII postcard on a private illustrated postcard; Lahore June 6, 1906 to Cannanore.